The voice mail was waiting on Amy’s phone one morning in February 2019, a missed call from her 18-year-old son the night before. When Amy, a mom from Connecticut who is being identified by first name only to protect her family’s privacy, played the message, she heard the panicked voice of her child.

Mom, he said, my face won’t stop twitching. I feel like I’m going to die. I’m trapped in another dimension and I can’t get out.

Terrified, Amy called the campus police at the University of Delaware. They found him asleep in his dorm room. Just a panic attack, they told her.

But she knew better. When she spoke to her son William, who is being identified by his middle name to protect his privacy, he told her: “I’m sorry. I think I just smoked way too much pot.”

Her son — an incredibly bright boy, a rule-abiding kid, a doting big brother — had started experimenting with marijuana as a junior in high school, Amy says. He told her it helped with his social anxiety, which intensified when he went to college, where he started smoking marijuana nearly every day. But the voice mail was the first time William had ever exhibited psychotic symptoms. About two months later, he called again with the same plea for help: He was trapped in another dimension, afraid he was about to die.

“My husband was like, ‘This isn’t from pot, no way, pot wouldn’t do this,’” Amy says. “But I’d started researching cannabis-induced psychosis, and I was like, ‘This is what’s happening.’”

That sense of disbelief — pot wouldn’t do this — is prevalent among parents who have watched their teenagers become gripped by addiction. But the landscape of teen marijuana use has radically transformed in the decades since today’s parents were teens themselves, and many Gen X’ers and millennials might not be attuned to what that means. A typical joint smoked decades ago contained less than 4 percent THC, the psychoactive compound in marijuana that causes the sensation of a high. Dried cannabis flower now averages closer to 15 to 20 percent THC, while the high-potency products most popular with teens — including THC-concentrated oils, edibles, waxes and crystals — often contain anywhere from about 40 percent to upward of 95 percent THC, an astronomical increase in potency that can have a significant impact on a developing adolescent brain.

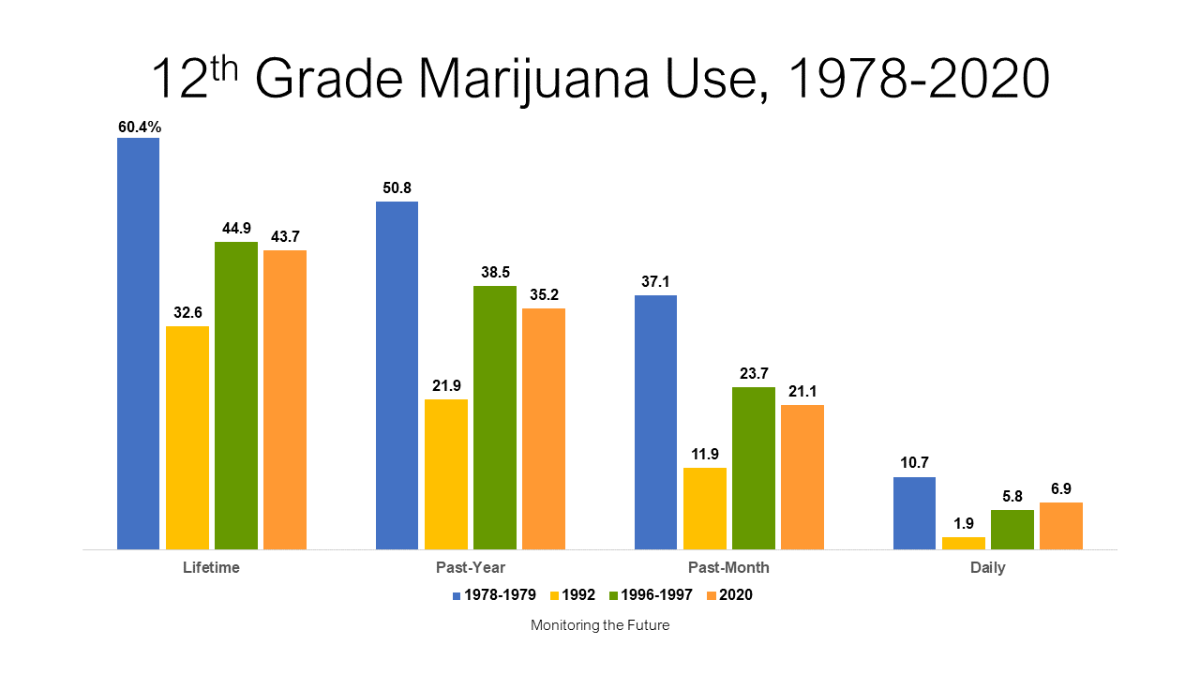

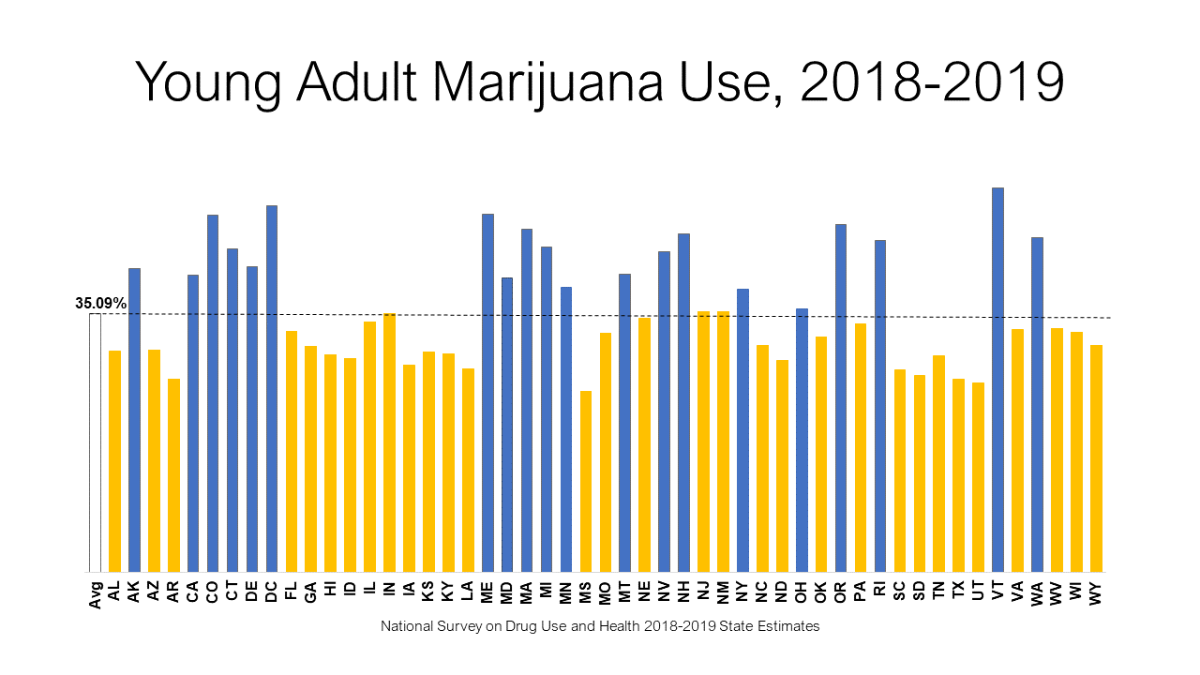

Meanwhile, the number of American teens using these products has soared in recent years. Research published in 2022 by Oregon Health & Science University found that adolescent cannabis abuse in the United States has increased by about 245 percent since 2000; a 2022 study by the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health found that, in 2020, 35 percent of high school seniors and 44 percent of college students reported using marijuana within the past year. That study also found that vaping was increasing as the most popular method of cannabis use.

Even as more families find themselves navigating the complex new reality of teen cannabis use, an antiquated cultural perception of the drug persists: Marijuana is medicinal, it’s natural, it’s not dangerous.

That’s what Laura Stack thought when her then-14-year-old son, Johnny, told her that he’d tried marijuana at a friend’s party near their home in Colorado in 2014, the same year that marijuana dispensaries first opened in their state. “I said to myself, ‘It’s just weed,’” she says.

She remembers what she told her child at the time: “‘Thank you for telling the truth, but please don’t ever do that again; you’ll ruin your brilliant mind.’” Privately, though, she wasn’t very concerned. “I’d used it when I was in high school, so I said to myself, ‘I used it, I’m fine, it clearly didn’t hurt me,’” she says. “I didn’t have any urgency around it. I was just so ignorant.”

[Potent pot, vulnerable teens trigger concerns in first states to legalize marijuana]

Johnny was a gifted, well-adjusted kid, Stack says, an excellent student with a perfect SAT score in math and a scholarship to Colorado State University. But by the time he was a senior in high school, he’d started vaping and “dabbing” — inhaling high-concentrate THC oil — multiple times per day, and his life unraveled. He developed paranoia, which progressed to psychosis, and he cycled through different treatment programs and hospitalizations as his family frantically tried to help him find a way back to himself. He was ultimately diagnosed with cannabis use disorder and cannabis-induced psychosis; he never tested positive for any other drug. He was put on antipsychotic medication, which helped, until he stopped taking it. In November 2019, Johnny leaped to his death from the top of a parking garage.

Stack has shared her son’s story with high school students and their parents countless times as the founder of Johnny’s Ambassadors, a nonprofit organization that seeks to educate parents and teens about the danger of youth marijuana use. “When we do a parent night or a community event, and I ask a crowd: How many of you know what ‘dabbing’ is? You’ll get just a few hands. And then the ones who raise their hands will say ‘Oh, I thought you meant the dance move,’” she says. “These parents just don’t know. They are just as unaware as I was.”

As an addiction develops, parents often describe a common pattern of decline and disengagement, the distortion of a teenager’s sense of self and personality as they grow removed from things they once cared about. M., a parent in California who is being identified by his middle initial to protect his family’s privacy, watched this happen to his youngest child, S., who is also being identified by his middle initial. S. was a good-natured and affectionate son, his father says, a diligent student and a star athlete who was on track to get a scholarship to a top-tier school; he dreamed of someday going pro.

S. started experimenting with marijuana as a high school sophomore. “He knew his big brother smoked, he knew his big sister did,” M. says. “He was curious. And it’s everywhere. It’s legal, right? It’s natural, right? It’s not meth or heroin.” M. felt he had a handle on what his children were using: “I grew up in the marijuana scene and I smoked weed, I smoked a lot of weed.”

But his son’s product of choice wasn’t the same plant buds that M. once knew; S. gravitated toward cannabis vape cartridges, flavored oils that left no scent in the air, so his parents wouldn’t detect when he was smoking. As his use progressed, fueled in part by his distress over athletic injuries, his behavior began to deteriorate. He grew increasingly hostile when his parents expressed concern. Then, one night in February 2022, S. didn’t show up to a school event, and the police later called to say they’d found him wandering a nearby neighborhood, shirtless in near-freezing weather, consumed by paranoid delusions.

Over the months that followed, M. says, the family endured a succession of traumatic episodes that have left lasting scars: There was the day S. was first hospitalized, when he FaceTimed his older sister in tears and told her that their parents wanted to call the police to take him to the emergency room; M.’s daughter cried as she tried to calm her little brother down, telling him, you need help. There was the second time S. experienced psychotic symptoms, when M. says his son appeared “demonic,” explaining with calm, chilling certainty that his mother had been partially possessed by an evil spirit, and he needed to “kill off” that part of her. There was the time M. was driving his son home, and S. kept begging his father to change lanes repeatedly, because he was convinced that driving behind certain cars would stop his body from itching.

This kind of account represents an extreme outcome — many teens, including S.’s two older siblings, might use marijuana without experiencing anything so severe — but psychotic symptoms themselves are hardly a rarity among adolescents and teens who use marijuana, says Sharon Levy, director of the Adolescent Substance Use and Addiction Program at Boston Children’s Hospital and associate professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School.

“I see kids with psychotic symptoms all the time,” she says. “It doesn’t mean they all have psychotic disorders, but it is scary.” In 2018, her team published a letter in the medical journal JAMA Pediatrics after surveying more than 500 children during their annual physical exams. Seventy teens who indicated that they had used marijuana “monthly or more” within the past year were asked a follow-up question: Had they experienced a hallucination or paranoia? “These symptoms are really psychotic symptoms,” Levy says, “and 60 percent of these kids said yes, they had experienced one or both of those.”

The impact occurs on a spectrum, Levy says: There are children who might experience hallucinations, delusions or paranoia as an acute symptom that resolves as soon as they’re no longer under the influence. There are teens who experience lingering psychotic symptoms, but can identify them as such — like one of Levy’s recent patients, a teen girl who thought that household objects were talking to her but recognized that this could not be real. And then there are the children like S., who develop psychosis that persists, and who no longer recognize that they are dissociated from reality.

“That’s the most severe form, and that’s the form that happens least commonly,” Levy says, “but I think as you move to lesser degrees of this, it’s actually fairly common.”

Teens are more vulnerable than adults to the impact of THC, Levy says, because the compound affects parts of the brain — the hippocampus, the prefrontal cortex — that are still undergoing structural development during adolescence. THC mimics a class of chemicals that the body naturally produces, Levy says, chemicals that guide the development of neurons in an adolescent brain. “Brain development is a very, very complicated process that we don’t fully understand, but we do know which areas of the brain are really rich in these receptors,” she says. When THC binds to those sites, “it interferes, it messes with the system.”

The lasting impact of this interference has been well documented, Levy says. “We’ve known for a very, very long time that the children who use cannabis products during their adolescence have worse outcomes across the board: They’re less likely to finish school, they’re less likely to get married and start a family of their own, they don’t do as well in the workplace.”

Any psychoactive compound has the potential to be addictive, Levy says, and while it’s true that some people can drink alcohol or use marijuana without developing a substance use disorder, the age of the user and the potency of the product matters: “When it comes to addictive substances, dose matters, and how quickly a dose gets to a brain really matters,” she says. “These highly potent products are much more addictive.”

Recreational cannabis use is illegal for those under age 21 in the U.S., but some studies indicate that children can more easily access the drug in states where it has been legalized. Some parents note that their children first accessed the drug through older friends or siblings who had obtained a medical cannabis card when they turned 18.

“The dramatic rise in adolescent cannabis use in 2017 really does coincide with the wave of decriminalization in the country,” says Adrienne Hughes, lead author of the OHSU study and assistant professor of emergency medicine in the OHSU School of Medicine. Beyond rendering the drug more accessible, she says, legalization has also “contributed to the perception that it’s safe.”

Levy believes the problem isn’t legalization itself, but rather a lack of sufficient regulation (Vermont and Connecticut are the only states to limit the potency of cannabis concentrate products). In certain states, she says, “the industry is very involved in regulating itself … which means that more and more products are available, and there is more confusing messaging to the population.” The result, she says, is that “marijuana is becoming more accepted by parents and kids, and it’s also more dangerous.”

But even for children who have been diagnosed with cannabis-induced psychosis, Levy says, there is hope of recovery; if they stay sober, their brains have the potential to heal.

That is what M. and his family are fiercely hoping for. M. estimates that he’s spent well over $100,000 on hospital and ambulance bills and rehab to try to save his son, who was diagnosed with cannabis use disorder and cannabis-induced psychosis. S. has been in an inpatient recovery center in California for about two months, and he’s doing better, M. says, but he still has months of treatment ahead of him.

There are moments when M. can envision a future for his son again: Maybe S. will attend community college, when he’s ready. Maybe he’ll study a foreign language — S. has sometimes said he’d like to live overseas, to get away from marijuana. “I’ve accepted the fact that he may never play [sports] again,” M. says, “but I really hope he does, because it really anchors him. It centers him. But I don’t know what’s going to happen.”

The rest of the family is still recovering, too. “It’s all so traumatic. We all have PTSD, we all have guilt, we’re all in counseling,” M. says. “This is what this does to a family.”

Amy, the mother from Connecticut, said she watched her son “slowly unravel” during his college years as his marijuana use continued to accelerate, leading to a psychotic break in November 2021. For the next year, William was in and out of emergency rooms, psychiatric wards and treatment centers, she says, a time she describes as all-consuming darkness.

“I was talking to all these doctors all around the state and around the country, all these residential treatment centers,” Amy says. “My purpose in life was to keep him alive until we could get him treatment that stuck.” He was diagnosed with severe cannabis use disorder, and doctors told Amy that his psychotic symptoms could be due either to bipolar disorder or cannabis-induced psychosis — the only way to be certain, they said, was to see if the symptoms abated once he was sober for a prolonged period of time.

Finally, in October, Amy and her husband brought their now 22-year-old son to Florida, where he is receiving treatment at an inpatient rehabilitation facility. Amy and her husband are staying with relatives nearby; Amy promised her son she’d stay close, that she’d wait for him to get better.

“They say that for the brain to heal, it literally could take a full year,” she says. “His improvement is vast, but he has a long way to go still.”

In the three years since Johnny Stack died, Laura Stack has seen the demand for her presentations grow. There are now more than 10,000 parent ambassadors affiliated with her nonprofit, she says, and a support group for parents of teens with cannabis-induced psychosis has grown to more than 500 members. She has become adept at reciting the latest research and the most startling statistics. She has learned what to share and what to say to help steer young lives in a safer direction.

But when she reflects on her own story, there are still questions she isn’t sure how to answer. Would it have mattered if they hadn’t lived in a place where it was so easy for her son to access these products? “But it’s everywhere,” she says, “so it really doesn’t matter where you live.” Then she wavers: “I don’t know, though. I wish I had moved.” She is quiet for a moment. “What I know,” she says, “is I would have done anything.”